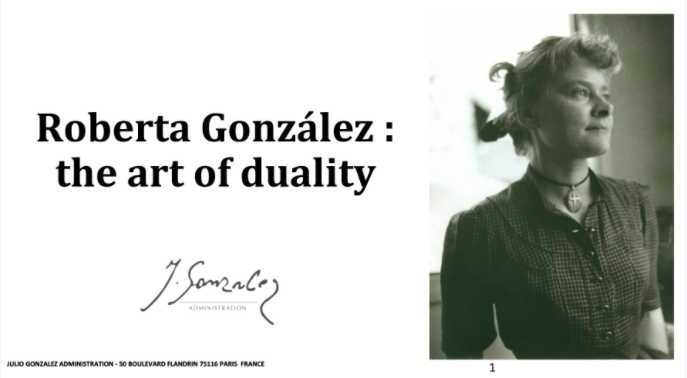

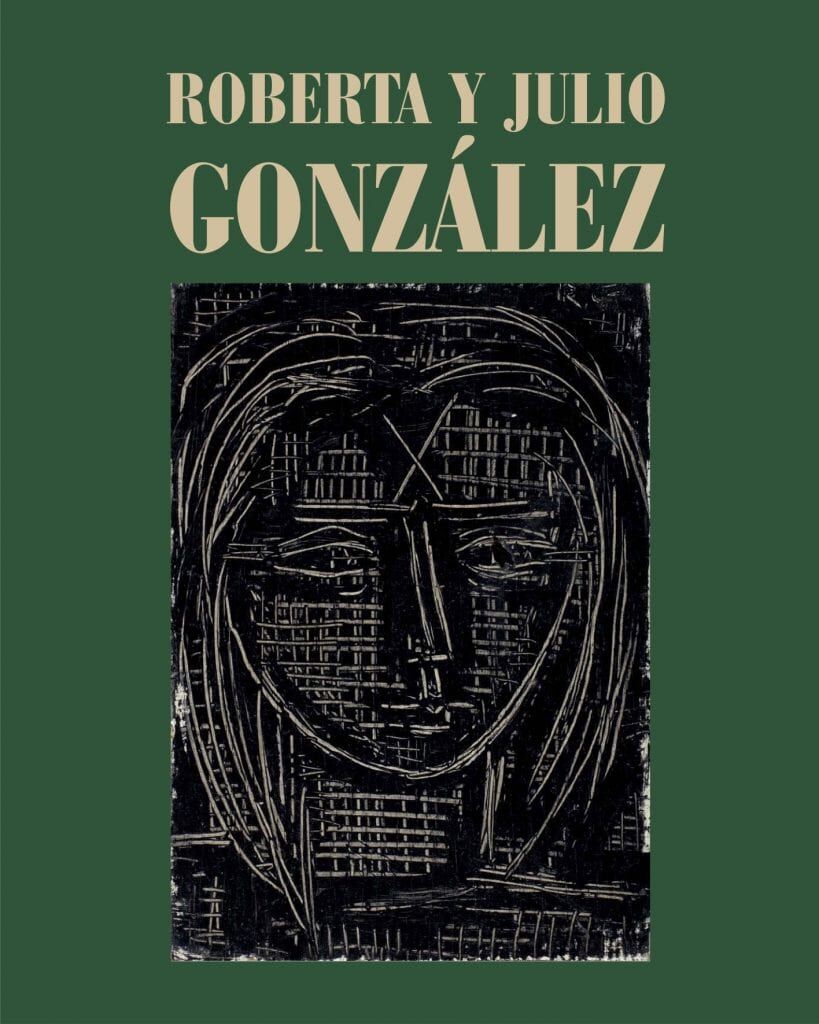

Roberta González (1909-1976)

Flip-book presentation: Roberta González, the art of duality

Roberta pursues the family vocation

J. González, Roberta et Pilar, 1914-18

Dessin de Roberta, 9 ans

(publié dans Les feuilles libres, 1924)

Roberta González is Julio González’s only child, born in Paris in 1909. Abandoned by her mother, Roberta grows up in a Catalonian enclave in Montparnasse, which in those years becomes an important avant-gardist hub. According to family legend, her childhood drawings are praised by Picasso, a longtime family friend. Indeed, Roberta pursues the family’s artistic vocation. Her father encourages her creative pursuits, often telling her: “you will become a painter and you will accomplish that which neither your oncle nor I have managed to express in painting”.

Roberta entre sur scène

Deux femmes et enfants, 1927

Angoisse, 1936

Visage anguleux, 1937

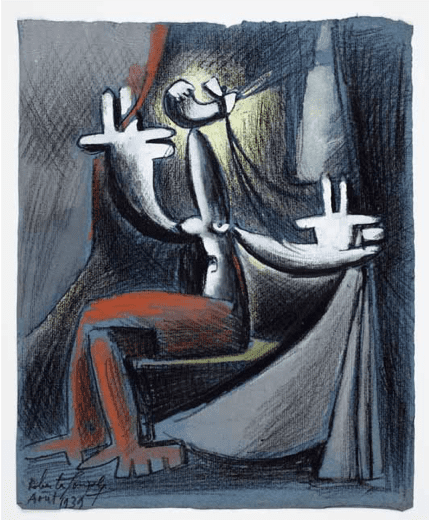

Untitled, 1939

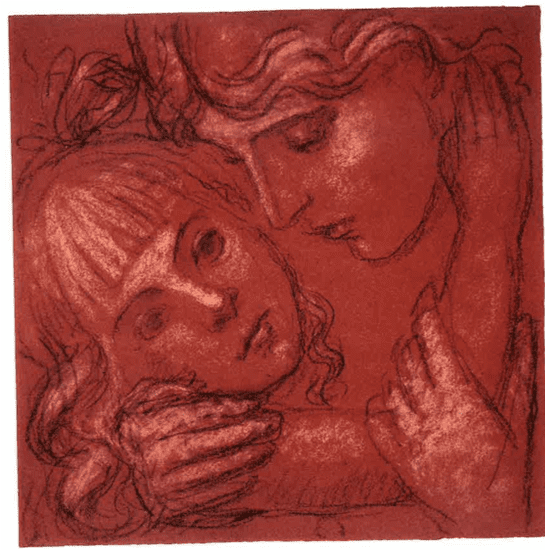

Roberta begins her career in the late 1920s. Her works were then similar in style and content to those of her father. Her early drawings and paintings, often representing peasants and mother and child scenes, are emblematic of her father’s classicism through the 1920s. Then, in the 1930s, like her father, she adopts a vanguardist style, influenced by Cubism and Surrealism, which deforms and shatters her figures. The introduction of this new style, communicative of distress and violence, coincides with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil war in 1936, which the González family follows closely from Paris. Her father takes an active role to defend Republican Spain alongside compatriot artists like Picasso, as Roberta later will as well.

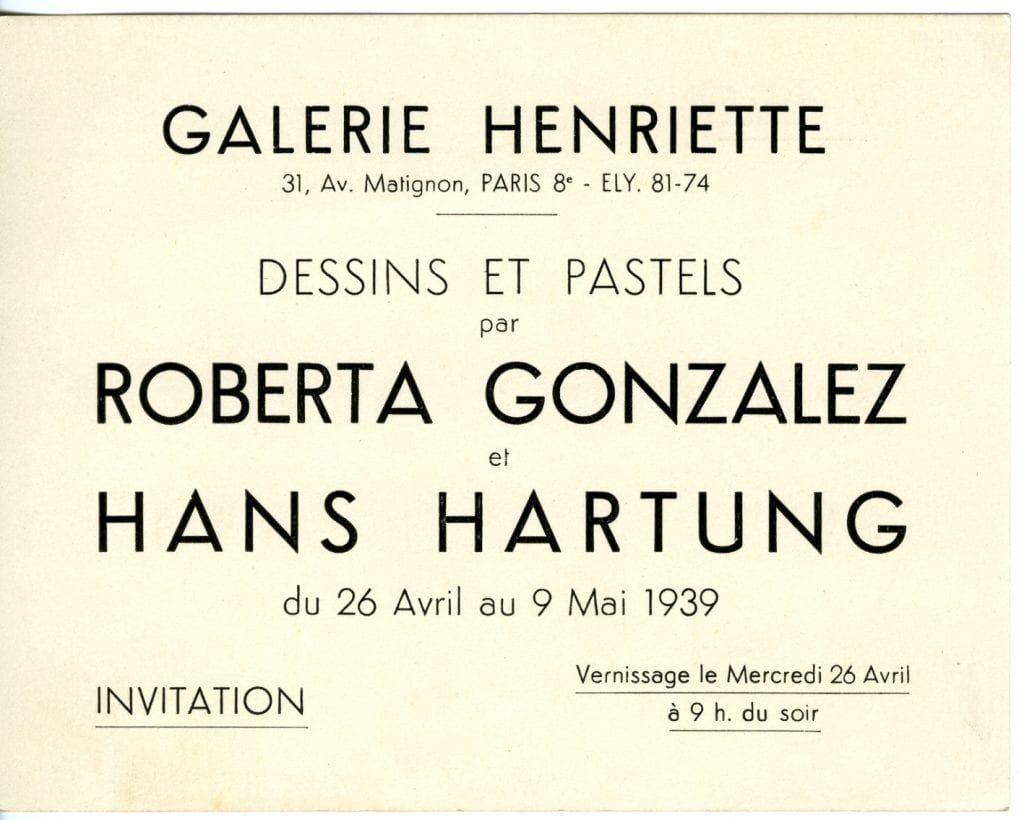

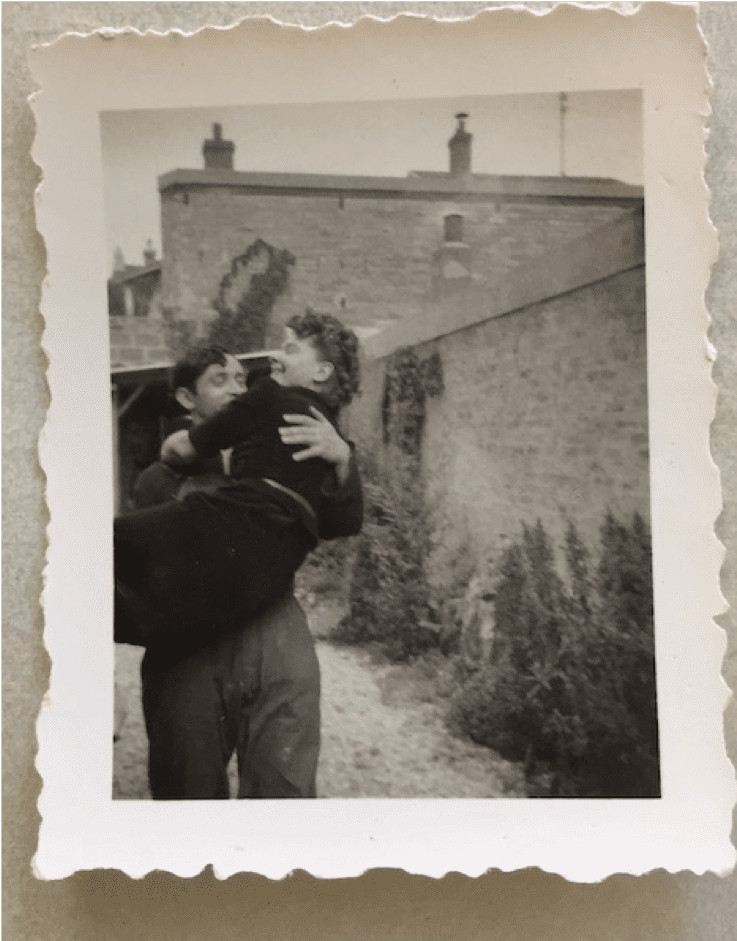

Roberta González et Hans Hartung

Her first personal exhibition takes place in 1939 at the Henriette Gomez gallery in Paris, along with the German abstract painter Hans Hartung, who frequents the Gonzalez studio and household, Julio having taken him under his wing. Roberta and Hans marry that same year.

A career interrupted by war

Soon after, their promising careers and their life as newly-weds are interrupted by the Second World War and the Nazi Occupation of Paris. The González family flees to the Lot at the outbreak of the war. Hartung, considered a traitor for having abandoned, and fought with the French Foreign Legion against, his country, is tracked by the Nazis, and unable to return to Occupied Paris. During this period, Roberta creates numerous family portraits while pursuing female subjects, whose shattered and deformed bodies testify to the violence of the time.

These war years, which profoundly impact Roberta’s life and work, are full of trials for her. In 1941, Julio González, eager to get back to his welded sculpture, which he was unable to pursue while in the Lot, returns to Paris. Roberta is therefore separated from her father when he unexpectedly passes away on March 27, 1942. Soon after, in response to the Nazi invasion of the South of France, Hartung is forced to flee to Spain. Roberta will only be reunited with her husband at the end of the war, when he is hospitalized for wounds sustained during the Battle of Belfort, that lead to the amputation of his leg.

Roberta’s introspective postwar work

La supplication, 1945-46

Jeune fille pensive, 1949

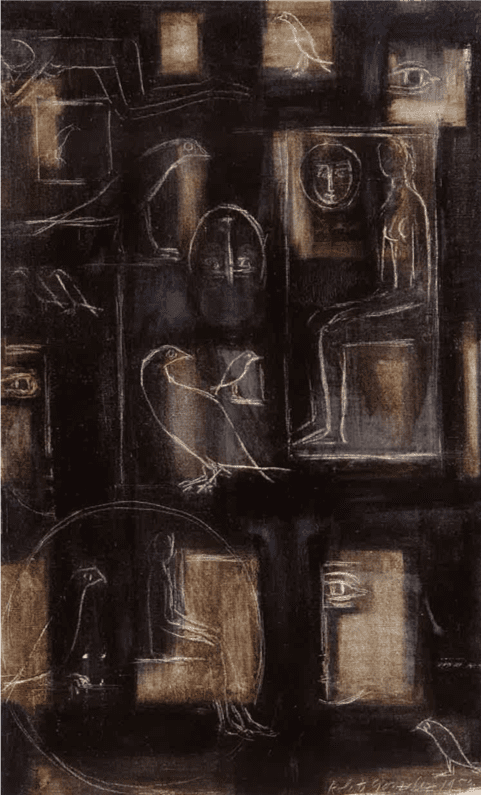

Sans titre, 1950

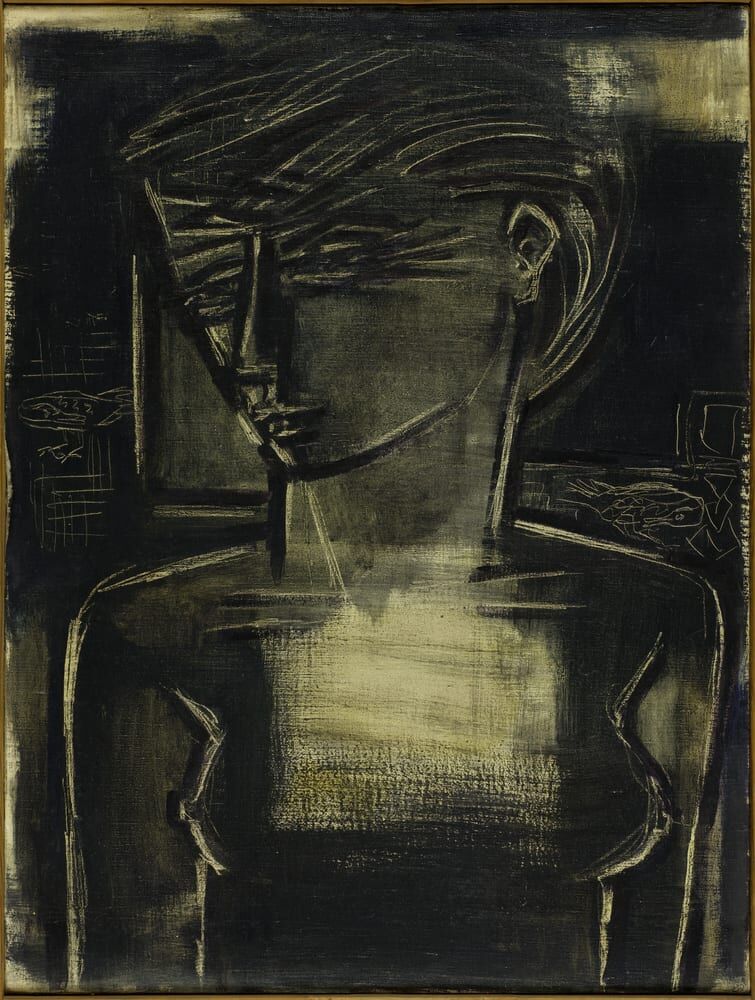

Back in Paris in the postwar period, Roberta returns to painting and drawing. She produces a series of stylized portraits featuring pensive and melancholic women, constructed with dark tones. These are a reflection of her state of mind after the dark years of the war and the devastating loss of her father. Slowly, the shadow of the war begins to fade. Her sharp angles evolve into softer, rounded formes, and she experiments with new techniques, like grattage.

Roberta’s postwar successes

The postwar years also mark her first important successes on the Parisian scene. She is featured in personal exhibitions at Parisian galeries like Jeanne Bucher (1948), Colette Allendy (1951) and Nina Dausset (1954), receives distinctions in several Paris-based art competitions, and participates in numerous collective exhibitions in Europe, the Americas and Asia.

The path to a personal style

Over the years, Roberta’s work shows an increasing impact of Hartung’s lyrical abstraction, which achieves great success in postwar Paris. As Roberta puts it, Hartung “opened a window on a new pictorial universe” for her. Without ever completely abandoning a link with observed reality, Roberta develops a unique plastic language in which figurative symbols and abstract signs exist in an undefined space, an abstract universe. She struggles all the while to add more color and joy into her work.

Color takes flight in Roberta’s mature works

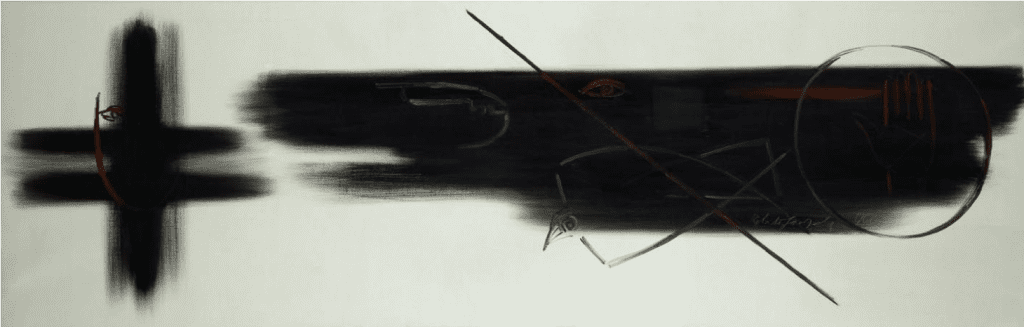

Les flèches no. 1, 1968

Les heureux citoyens du monde, 1973

Her personal style between figuration and abstraction reaches its maturity in the 1960s and early 1970s. Her mature works are colorful, expressive and dynamic, full of joy, poetry and humor, just like the artist herself.

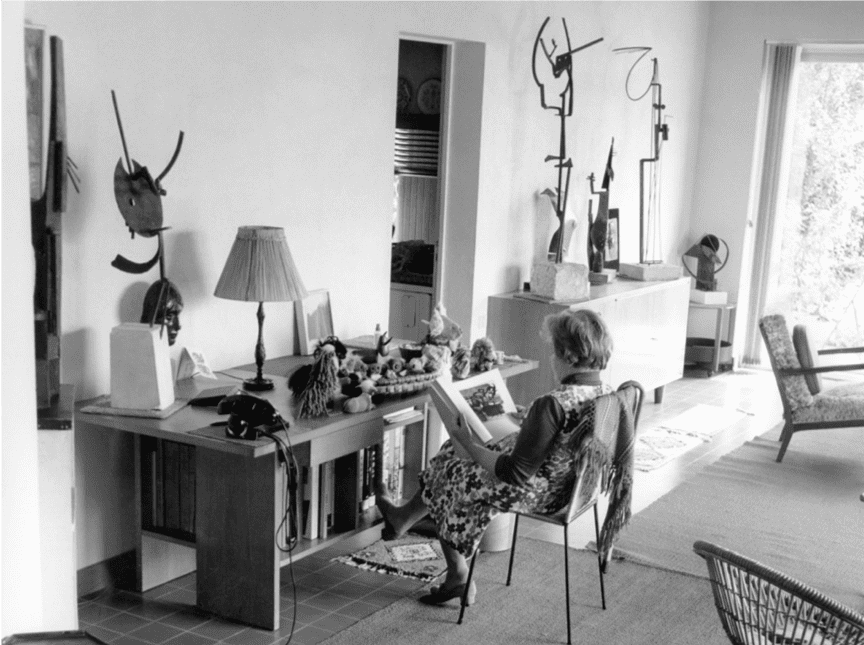

Promoting the family legacy

All the while, Roberta works tirelessly at the promotion of her father, and later, her oncle’s, work. She organizes exhibitions and makes important donations of the González family’s work to collections in France, Spain and abroad. She is successful in her efforts, as her father gains recognition for his pioneering role in modern sculpture.

Roberta González’s return “sur scène”

Roberta Gonzalez prioritized the promotion of her father’s work over her own. Nonetheless, in recent years, she has been increasingly present on the international art scene.

Her works are today housed in prestigious collections like the Centre Pompidou Paris, the IVAM Centre Julio González and the Fondation Maeght.

Roberta González was featured in two solo shows in 2012, at the IVAM Centre Julio González and the musée Arts et Histoire de Bormes-les-Mimosas. She builds a modernist villa in this village in the French riviera based on her own plans.

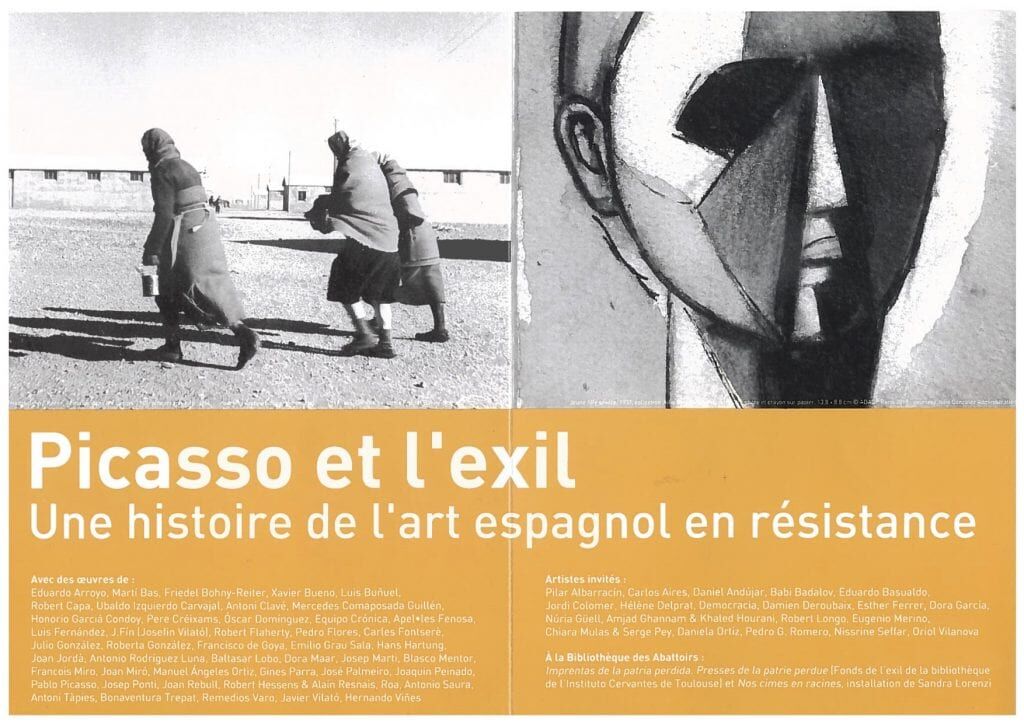

In 2019, a dozen of her paintings and drawings were featured in the highly successful exhibition “Picasso et l’exil. Une histoire de l’art espagnol en résistance”, which took place in Toulouse, at the musée les Abattoirs, from March 15 to August 25, 2019. At the same time, her wartime work was featured in a conference at Paris’s Army Museum , as part of their cycle on 20th century artists and war.

Nu mélancolique, 1950

Her work is currently displayed at the Centre Pompidou Málaga in their exhibition retracing a century of Spanish art (« De Miró a Barceló. Un siglo de arte español »).

Soon, Mexico will be able to discover Roberta González’s work when the “Picasso and exile” exhibition is presented in a modified form at the INBAL Modern Art Museum of Mexico City. This exhibition, initially planned to open in July 2020, has been delayed because of the pandemic.