“Hans Hartung, ou la fabrique du geste” is a major retrospective held at the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris (MAMVP) from October 11, 2019 through March 1, 2020. The first in 50 years, the show is an ideal occasion to retrace not only Hartung’s impressive career, but also the important artistic and familial ties that bind the German-born artist and the González family.

As for the exhibition, the 300 works displayed cover the entirety of Hartung’s career. His pioneering role in abstract art in France is highlighted, as well as his constant experimentation and innovation, in terms of his painting techniques and practices, as well as with other media, like photography, print and ceramics.

Glimpses of Hartung’s close relationship with the González family also shine through. The story begins in 1937, when Hartung presents himself to Julio González, whose work he admired. González takes the young Hartung under his wing, and introduces him to his groundbreaking autogenous welding technique that he used to revolutionize 20th century metallic sculpture.

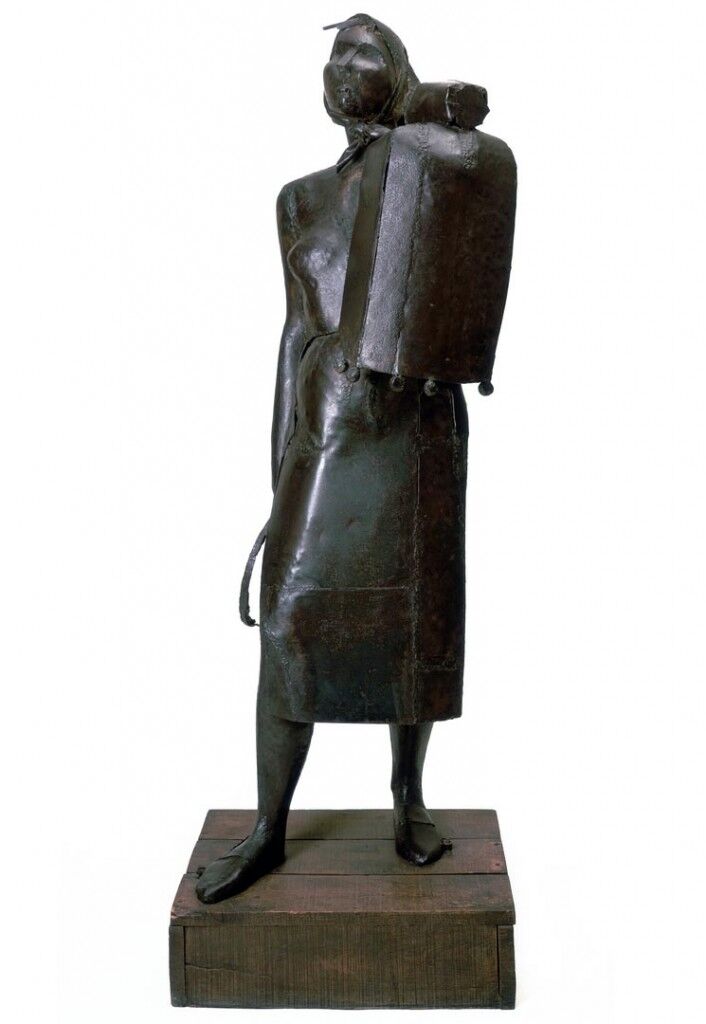

Roberta González, Maternité,

ca. 1936, MNAM

J. González, La Montserrat, 1937

Under González’s tutelage, Hartung produces an iron sculpture of his own, on display in the exhibition, in his characteristically abstract style (Untitled, 1938). González was in the habit of indoctrinating other artists to his signature practice, both young and experienced. For example, he introduced his long-time friend and compatriot Pablo Picasso to his innovative welding techniques at the end of the 1920s, when they collaborated on a series of metallic sculptures initially destined for Guillaume Apollinaire’s funerary monument. He had also assisted his daughter, Roberta, she herself an artist, in creating a metallic Maternity piece around 1936. This work is a sort of prelude to his own famous iron sculpture Montserrat, revealed to the world at the same occasion as Guernica in 1937 at the Paris World’s fair.

These two works created under González’s tutelage are extremely different, and reveal the two distinct artistic visions defended by Hartung and Julio González. In spite of the respect each held for the other, Hartung was an adamant defender of abstraction, while Julio González believed in the necessity of drawing from Nature as a constant point of departure. In her early works, Roberta González adhered mainly to her father’s philosophy, as her Maternity shows, but she would later be influenced by the abstract style practiced by the young German artist who quickly became a regular in the González household. According to Roberta González, Hartung exposes her to a new pictorial universe.

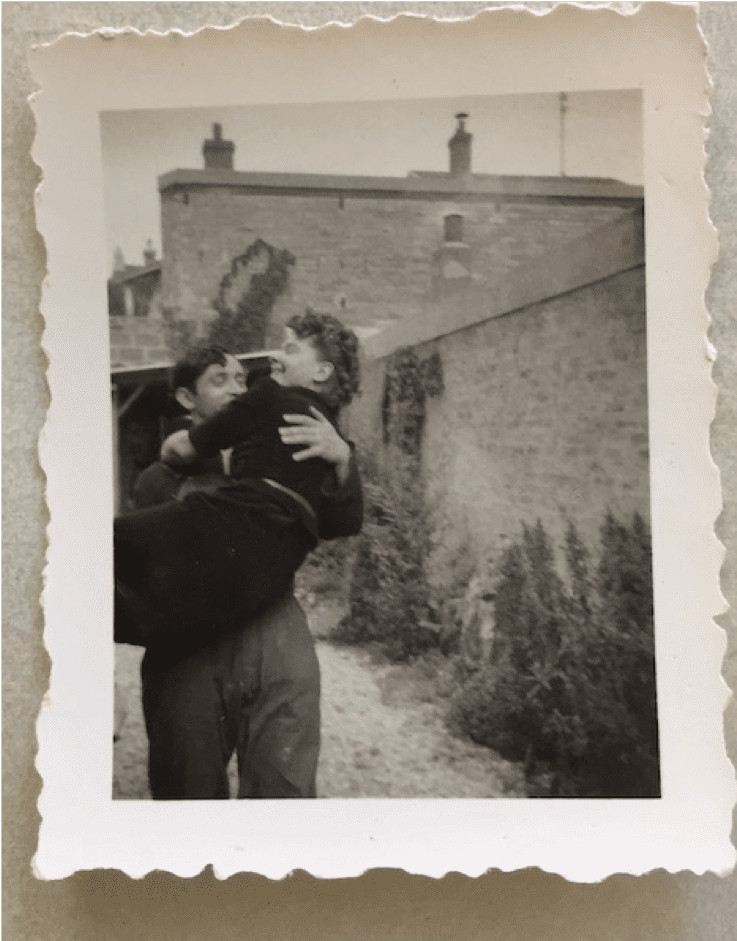

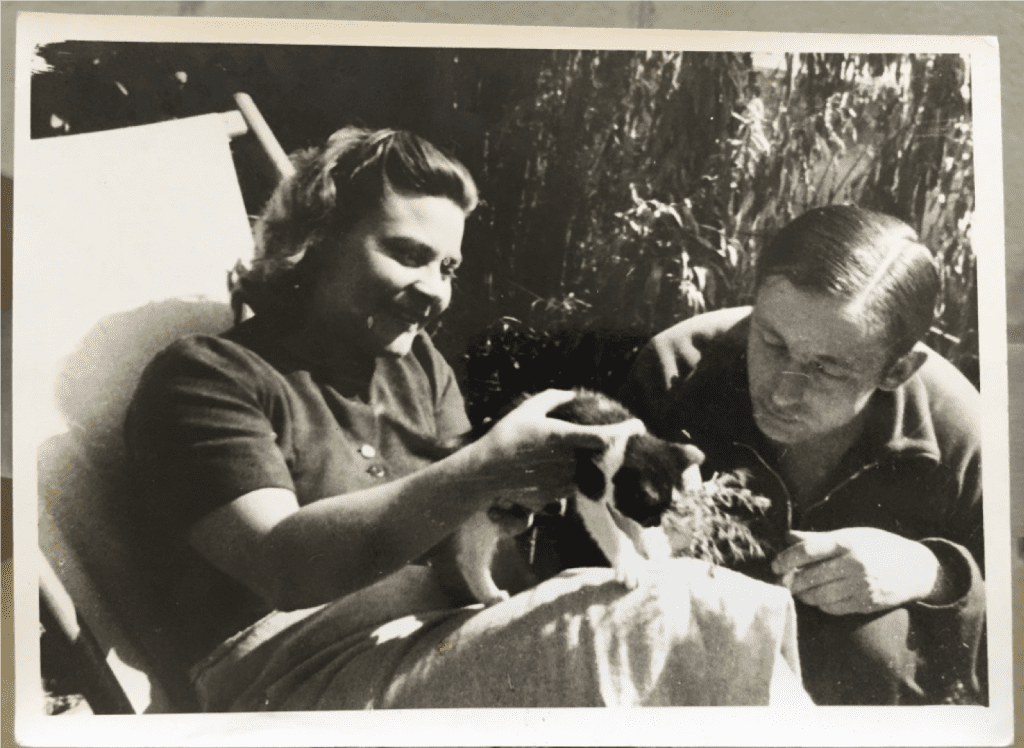

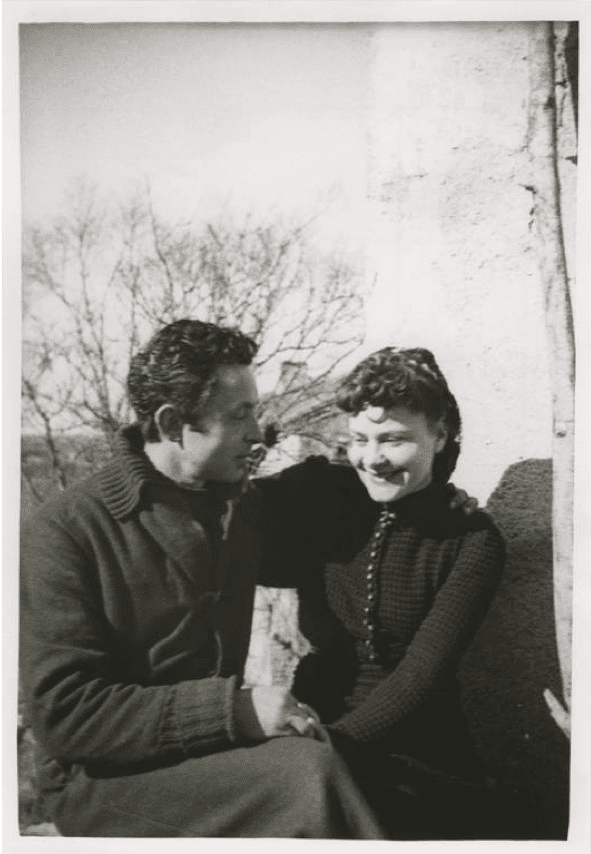

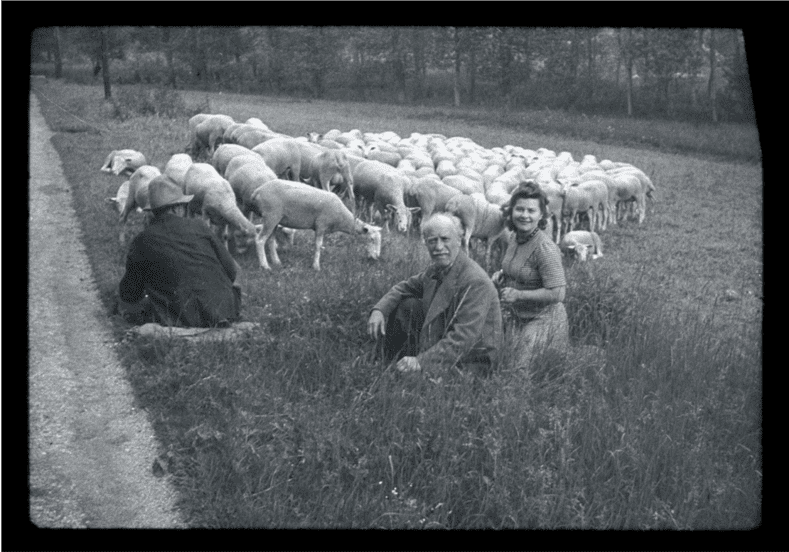

Indeed, Hans and Roberta grew increasingly close. The exhibition displays photographs that document their early relationship, including some from the González Estate’s private archives.

R. González, Jeune fille sévère, 1937

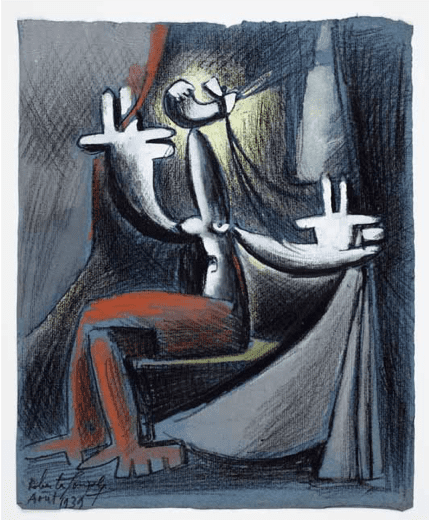

R. González, Untitled, 1939

Since the outbreak of the Spanish Civil war in 1936, Roberta’s work had been largely influenced by her father’s wartime production; her paintings and drawings were full of sullen or screaming women whose forms were shattered and deformed with a Cubo-Surrealist style that reflected the violence and distress of the war.

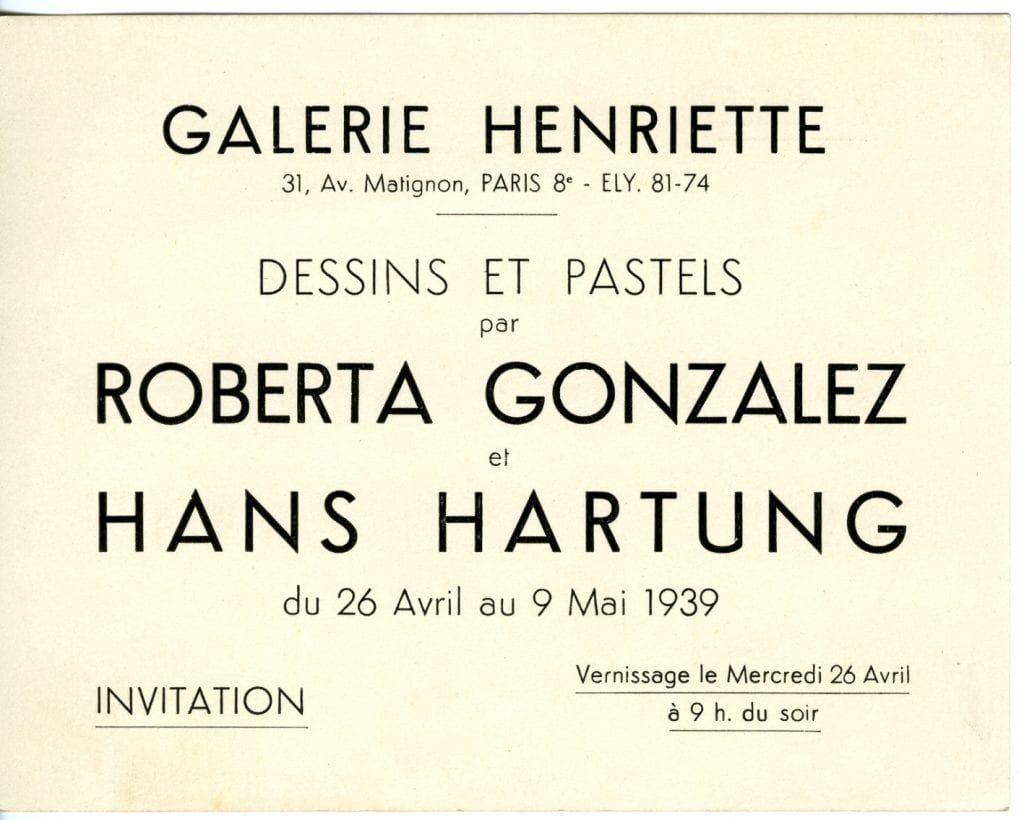

After an exhibition together at the Henriette Gomez gallery in Paris, Roberta’s first nearly-solo show, the young artists were married in 1939. However, their happiness was quickly shattered by the outbreak of World War II, which repeatedly separates them.

Hartung in the Foreign Legion uniform, Algeria, 1940

Hartung & Roberta González-Hartung, 1942, Lasbouygues

First, Hartung, a staunch anti-fascist, joins the French Foreign Legion. Then, unable to return to Occupied Paris after the armistice, Hartung and the entire González family take refuge in unoccupied France.

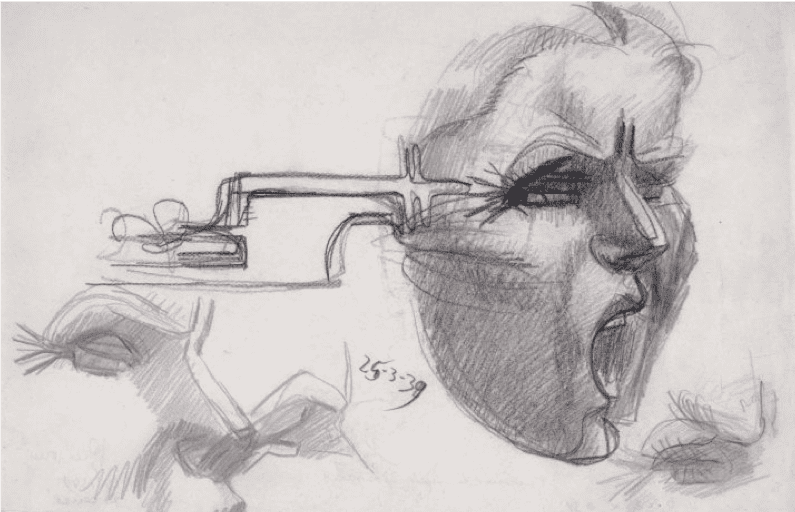

Julio González, El grito (The scream), 25.3.1939

Hans Hartung, Untitled, 1940

R. González, Vierge douleureuse, 1941

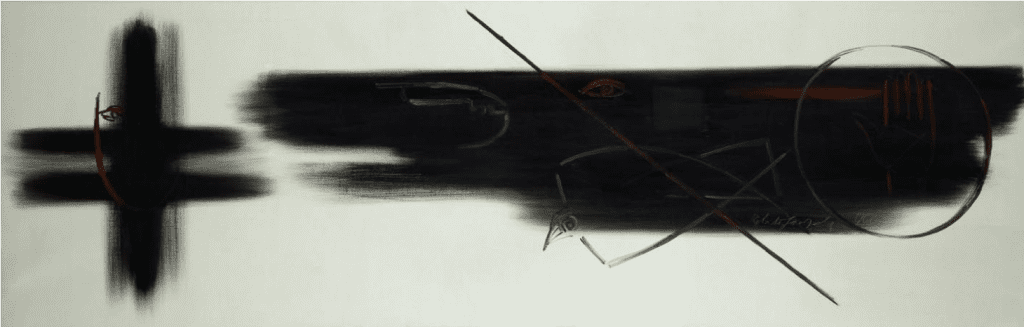

The uncertainty and anxiety of the time continues to be reflected in the works of Hans, Roberta and Julio González. As the 2019 exhibition “Picasso and the exile,” showed in a room devoted to the Hartung-González’s experience in exile, Hartung produces a series of “Gonzaloïd” works, including paintings and drawings of sculptural, abstract forms and Cubo-Surrealist heads, influenced by his father-in-law’s sculptures and drawings. Roberta continues in the same vein.

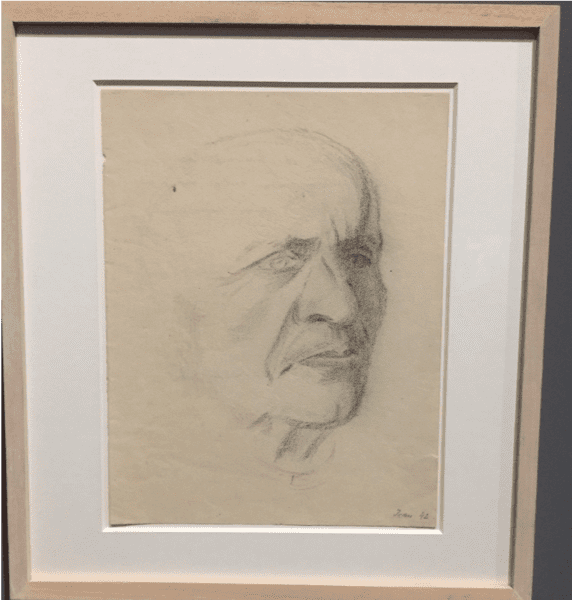

Hans, Roberta and Julio also create numerous portraits of the González family. The display of these works in the MAMVP exhibition attest to this rare figurative interlude in the career of Hartung, who espouses abstraction early on. It also testifies to the artistic exchanges between Hartung and González, who passes away unexpectedly in 1942.

Hartung, Portrait of J. González, 1942

R. González, Portrait of my father, 1941

R. González, Portrait of Tía Pilar, 1942

Hans and Roberta are separated once more when he is forced to flee to Spain in 1943, when the Germans invade unoccupied France, where he is promptly imprisoned. Upon his release, he joins the Free French Forces, returns to France, sustains a wound on the battlefield, and ultimately loses his leg. He is only reunited with Roberta in late 1944.

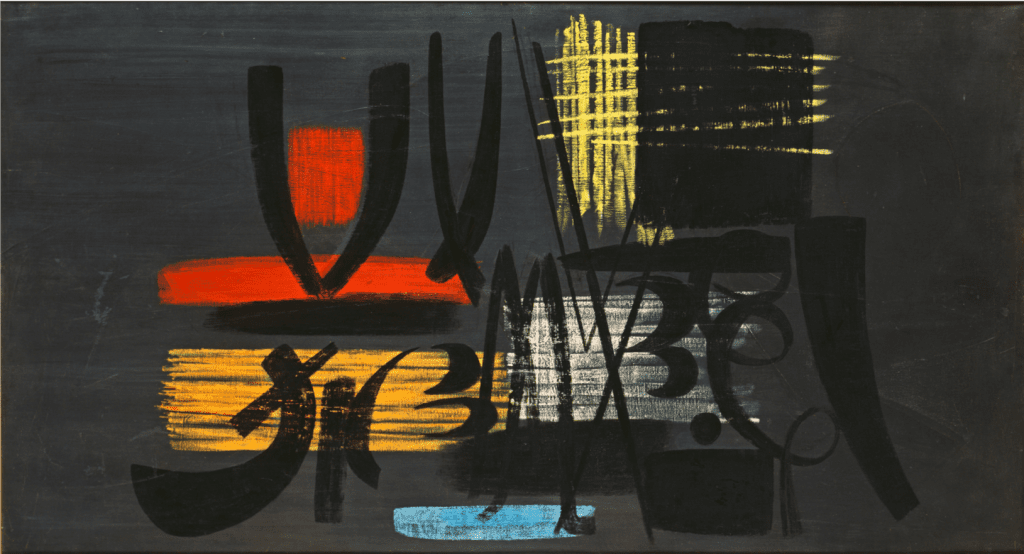

After the war, Hans and Roberta return to the Parisian region and resume their respective careers. Hans finally achieves the success that eluded him before the war, becoming the leader of Paris’s “Lyrical Abstraction” movement, which promotes spontaneous, dynamic and expressive non-figurative paintings.

In the meantime, Roberta González struggles to find her own personal style and to heal after the trauma of the war.

R. González, La supplication, 1945-6

R. González, Jeune fille pensive, 1949

Her initial works are in keeping with her fragmented and anxiety-ridden wartime style, but little by little, she begins to experiment with her own artistic language.

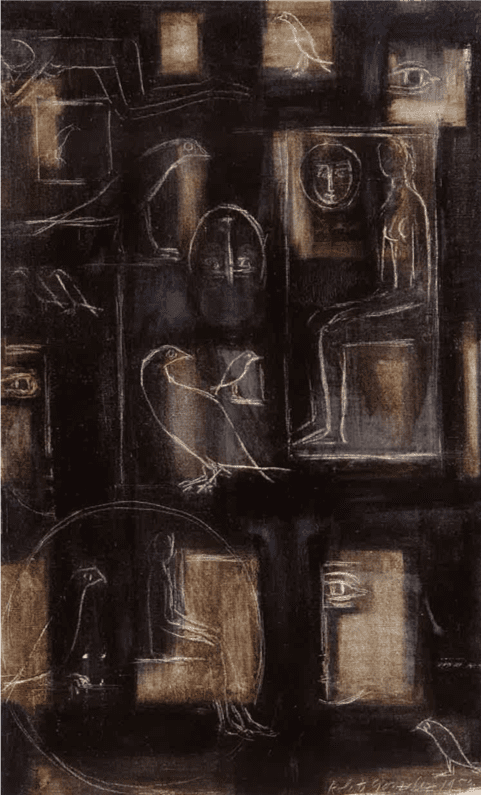

R. González, Untitled, 1952

R. González, Léda no. 3, 1952

This new, personal style assimilates her father’s insistence on figuration with elements of Hartung’s abstraction. Concretely, Roberta González develops a largely figurative artistic vocabulary, composed of suns, masks, profiles, arrows and other signs, that float in an undefined space, among color blocks applied with visible, dynamic gestures, like in Hartung’s painting.

Roberta González, The Blue Stain, 1956

Roberta González, Burning Torso, 1967

Roberta González and Hans Hartung divorce in 1956, after Hartung rekindles his relationship with his first wife, artist Ana Eva Bergman. Nonetheless, Roberta González remains on friendly terms with the Hartung-Bergman’s until the end of her days, as their ample correspondance conserved at the Fondation Hartung-Bergman attests. Roberta González’s artwork testifies to the importance of her encounter with Hans Hartung, who helps her find her own, personal artistic style and voice.