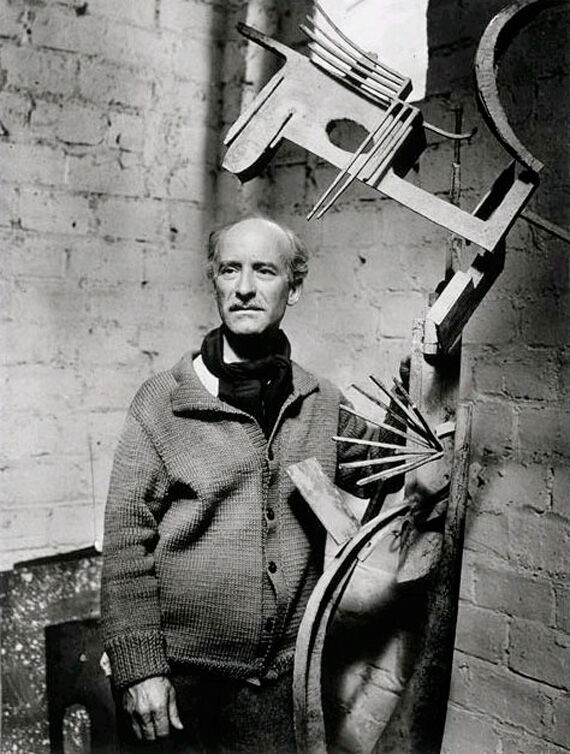

Rogi André, Portrait of Julio Gonzalez, c. 1937

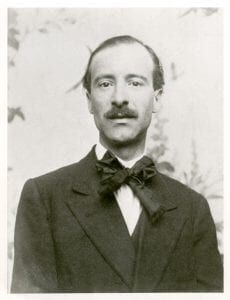

Julio González, c. 1920-1925

Julio González with a cat at his home-studio in Arcueil, c. 1937-1939

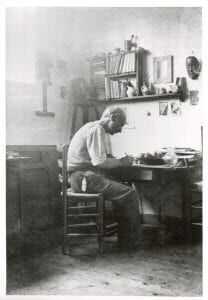

Julio González in his workshop in Arcueil, c. 1937-1939

Julio González in his workshop in Monthyon, 1928-1935

Julio González & Hans Hartung in González's workshop in Arcueil, c. 1937-1939

Julio GONZALEZ (1876-1942)

From decorative metal-worker in Barcelona to multimedia artist in Paris

Julio González begins his career as an artisan metalworker in the family workshop in Barcelona, alongside his brother, Joan. At the same time, they take evening painting and drawing classes, in hopes of one day becoming "real" artists. They frequent Barcelona's effervescent artistic and intellectual milieu, largely centered around the artistic cabaret "Els Quatre Gats", founded by Modernist painters Santiago Rusinol, Ramon Casas and Miguel Utrillo.

After their father's death, the González brothers decide to sell the family business and pursue their shared dream by moving to Paris, then the undisputed capital of the arts. In 1900, the whole González family picks up and settles in Montparnasse, a bohemian neighborhood on the southern outskirts of the city that was transforming in those years into Paris's new avant-gardist hub. The two brothers reconnect with artists Pablo Picasso, Manolo Hugué, Pablo Gargallo, and Joaquin Torres-Garcia, friends from Barcelona, as well as writers and critics, like Max Jacob. González exhibits for the first time at the Salon des Indépendants in 1907, showing six paintings.

When Joan succumbs to his fragile health in 1908, Julio is devastated, but carries on. The following year, he marries Louise "Jeanne" Berton, a French woman who had worked as his model. Though their marriage doesn't last, their daughter, Roberta, is born in 1909. Roberta goes on to be raised by her father and aunts in a Catalan enclave in Montparnasse.

In the years leading up to World War I, González pursues diverse artistic forms : painting, drawing, decorative metal-work, and sculpture. González executes his first metallic mask in 1912 using the repoussé technique. He exhibits in various Parisian salons, including the Salon d'Automne, thanks to the influence of the writer, poet and sculptor Alexandre Mercereau, who becomes his agent in 1911. He presents himself as a painter, decorative metal-worker and/or sculptor. González frequents the Closerie des Lilas, a mythic literary and artistic café in Montparnasse, to exchange ideas with his colleagues Modigliani and Brancusi, with whom he collaborates closely over the years. González's work begins to attract the attention of collectors and critics. In 1918, he learns the oxyacetylene welding technique in a factory in Boulogne-sur-Seine, which will have a significant impact on his career.

The artist takes flight

In the interwar period, González pursues and perfects his multi-faceted artistic practice. His first personal exhibition takes place in March 1922 at the galerie Povolozky, marking the beginning of his recognition on the Parisian scene. In the catalogue, his friend and agent Alexandre Mercereau writes: “Julio González is an amazing man. Endowed with a dazzling imagination, a multiplicity of means of translation, he is a painter, sculpture, architect, glass and faience-worker, furniture maker. He casts, hammers, works in repoussé various metals, like iron, copper, gold, and silver, as well as wood, he designs dresses and embroidery and, what’s more, he is so modest that, in the 20 years since he has arrived from Barcelona, city of his birth, to Paris, he hides it so well […] that one can frequent him for ten years without knowing anything of his artwork, which he has only decided to display in recent years, thanks only to the insistence of his obstinate friends ». Well received in the press, another personal exhibition follows in January 1923 at the galerie Le Camélion, in addition to salons and collective shows, both in Paris and Barcelona.

At the same time, González experiments with his sculpture, applying to it the oxyacetylene welding technique. This innovative application of an industrial technique to an artistic practice allows González's sculpture to reach new heights in the interwar period. In 1929, González abandons painting, deciding to devote himself entirely to sculpture. He signs a contract with the Galerie de France the same year, promising to devote to them the entirety of his production for the next three years. He displays his iron sculpture there in 1930 for the first time.

Simultaneously, González and Picasso engage in a fruitful artistic collaboration. From 1928 to 1932, they work together on metallic sculptural constructions in response to Picasso's commission for Guillaume Apollinaire's funeral monument. In exchange for his savoir-faire in industrial welding, this collaboration with Picasso, avant-garde inventor and master, helps González develop and hone his personal sculptural language, which translates forms from observed reality into abstractions. As the celebrated critic André Salmon writes in Gringoire (May 18), Gonzalez's "forged iron sculptures, visibly abstract, [...] are in fact poems to nature".

Salmon's observation comes in response to "J. Gonzalez. Sculptures", a personal exhibition at the galerie Percier held in April-May 1934. In the exhibition catalogue's preface, the critic Maurice Raynal refers to González as "the artist of the void". Indeed, the application of this industrial technique to his artistic practice allows González to incorporate space as a constructive element into iron sculpture.

González exhibits again in a solo show at the galerie des Cahiers d'art at the end of 1934, once again drawing praise from Salmon, who writes: "Having waited a long time, González has finally revealed himself in a relatively precipitated way. We dare to hope that this second exhibition will definitively position this artist for greatness. He mustn’t only occupy a privileged position in relation to his compatriot Gargallo, who expresses in stone what González expresses in forged iron; González’s work must be inscribed in the history of modern art both as the most spontaneous of plastic efflorescences and the most lucid demonstration of that which has been called cubism, which extends so far beyond the constructive experiments of 1910 “.

While his production is certainly influenced by cubism, constructivism, surrealism, and other aesthetic movements flourishing around him, González refuses to conform to any sole style or current. His creative process is dictated by his personal vision, and as such, González’s mature works are unclassifiable. Nonetheless, in the mid-1930s, as Salmon indicates, González seems poised for greatness. His presence intensifies on the Parisian scene and beyond, as his work attracts the attention of American curators, critics and collectors, like Albert Gallatin, James Johnson Sweeney, and Alfred Barr, who acquires González's Tête dite "l'Escargot" (1935) for New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1937.

Caught in the tumults of history: Political engagement and a promising career cut short

That same year, González expresses his solidarity and support on the world stage for the second Spanish Republic under attack by the rebel nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War. Like Picasso's Guernica (1937), his iron sculpture La Montserrat (1936-1937), depicting a determined, resilient Catalan peasant woman holding a child, occupies a place of honor in the Spanish Republican Pavilion in the 1937 World's Fair in Paris. The theme of the Montserrat remains González's preferred subject to express his distress before the violence and tragedy of the war, first in Spain, then in Europe.

Indeed, Julio González doesn’t have time to make a lasting name for himself before his production is curtailed and career interrupted by the tumults of the 20th century. He must flee from Paris with his family in anticipation of the Nazi Occupation in 1940; his son-in-law, the German abstract painter Hans Hartung, was wanted as a traitor by his compatriots. The entire González family settles in the Lot. Though Roberta and her aunts, Julio's sisters, remain there for the duration of the conflict, González, eager to resume his iron sculpture, returns to Paris in 1941. He resumes contact with Picasso and his compatriots before his career is definitively cut short by his untimely death in 1942, at the age of 66. In the Postwar, in recognition of his pro-Republican engagement, his compatriots include his works in their numerous anti-Franco artistic exhibitions, which extend from Paris to Prague.

In the Postwar period, Roberta González works tirelessly to promote her father's work, in hopes of attaining for him the recognition that his revolutionary work deserved. She collaborated on the organisation of major retrospectives in numerous countries and several continents, and made donations of his work to prestigious institutions. Today, González's work is present in the world's most renowned museums, institutions and collections.